Functions

- Press O or Escape for overview mode.

- Visit this link for a nice printable version

- Press the copy icon on the upper right of code blocks to copy the code

Class outline:

Review

Data types & values

Programs manipulate values.

Each value has a certain data type.

| Data type | Example values |

|---|---|

| Integers | 2 44 -3

|

| Floats | 3.14 4.5 -2.0

|

| Booleans | True False

|

| Strings | '¡hola!' 'its python time!'

|

Expressions & operators

Python evaluates expressions into values in one or more steps.

| Expression | Value |

|---|---|

'ahoy'

| 'ahoy'

|

'a' + 'hoy'

| 'ahoy'

|

7 / 2

| 3.5

|

Mathematical operators

| Operator | Name | Example |

|---|---|---|

| + | Addition | 1 + 2 = 3 |

| - | Subtraction | 2 - 1 = 1 |

| * | Multiplication | 2 * 3 = 6 |

| / | Division | 6 / 3 = 2 |

| % | Modulus (divide & return the remainder) | 5 % 2 = 1 |

| ** | Exponentation (aka powers) | 2 ** 3 = 8 |

| // | Floor division (divide & round down to the nearest integer) | 5 // 2 = 2 |

Variables

A name can be bound to a value.

A name that's bound to a data value is also known as a variable.

One way to bind a name is with an assignment statement:

| x | = | 7 |

| Name | Value |

The value can be any expression:

| x | = | 1 + 2 * 3 - 4 // 5 |

| Name | Expression |

Naming conventions for variables & functions

- Use a lowercase single letter (variables only), word, or words

- Separate words with underscores

- Make names meaningful, ex

first_namerather thanfn

Examples

m(variables only)hobbymy_fav_hobby

See more examples at Real Python: https://realpython.com/python-pep8/#naming-styles

Built-in functions

Python has lots of built-in functions. Built-in functions are not specific to a particular data type - they often work on multiple data types (but check the docs!)

Some examples are:

pow(2, 100)

max(50, 300)

min(-1, -300)

Importing functions & modules

Some functions from the Python standard library are available by default. Others are included with a basic Python installation, but need to be imported into your current file before they can be used.

Import a single function from the Operator module :

from operator import add

18 + 69

add(18, 69)

Debugging with print()

One of the most commonly-used built-in functions is print()

We use print() to tell Python what to output to the console. This is very useful in debugging - ex, to see the value of a variable.

print("hello world")

x = 5

y = 10

print(x)

print(y)

print(x+y)

Built-in methods

Each data type has a set of built-in methods that only work on that data type. Check the Python data types docs to see which methods are available for a given data type.

Examples of string methods are:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| .upper() | Returns a copy of the string with all characters converted to uppercase |

| .lower() | Returns a copy of the string with all characters converted to lowercase |

| .title() | Returns a titlecased version of the string where words start with an uppercase character and the remaining characters are lowercase |

| .swapcase() | Returns a copy of the string with uppercase characters converted to lowercase and vice versa |

| .strip() | Returns a copy of the string with the leading and trailing whitespace characters removed |

Syntax tips

String syntax

Make sure you wrap strings in quotes. Otherwise Python will think it's the name of a variable or function.

Quotes can be single or double, just be consistent.

| Uh-Oh | Correct |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comment syntax

A comment is human-readable text that's ignored by the Python interpreter.

# A single-line comment starts with a hash sign

x = 4 # A comment can also go at the end of the line

"""

Multi-line comments

start and end with three quotes.

"""

Commenting out

A common programming practice is to "comment things out" while debugging code. That allows you to see how your program works without a line of code and see whether that affects the execution or fixes a bug.

x = 5

y = 10

#z = x ** y

z = pow(x, y)

Documenting with comments

Programmers often use comments to explain segments of code that aren't obvious.

h = 50 # Hue from 0-360

s = 99 # Saturation from 0-100

v = 50 # Value from 0-100

Functions intro

What is a function?

A function is a sequence of code that performs a particular task and can be easily reused. ♻️

We've already used functions!

add(18, 69)

mul(60, sub(5, 4))

A function takes input(s) (the arguments) and returns an output (the return value).

18, 69 → add → 87

Why functions?

Consider this function-less code:

greeting1 = "Hello, Jackson, how are you?";

greeting2 = "Hello, Dr. Biden, how are you?";

greeting3 = "Hello, Stranger, how are you?";

Functions help when code has repetition.

Function parameters help when that repetitive code has variation.

Building a function

First identify the repetitive parts:

def say_greeting():

return "Hello, how are you?"

Then use parameters for the parts that vary:

def say_greeting(name):

return "Hello, " + name + ", how are you?"

Finally, test it with different arguments:

greeting1 = say_greeting("Jackson");

greeting2 = say_greeting("Dr. Biden")

greeting3 = say_greeting("Stranger")

Defining functions

Defining functions

The most common way to define functions is Python is the def statement.

def <name>(<parameters>):

return <return expression>

Example:

def add(num1, num2):

return num1 + num2

Once defined, we can call it:

add(2, 2)

add(18, 69)

Anatomy of a function definition

The first line is called the function signature, all lines after are considered the function body.

def <name>(<parameters>): # ← Function signature

return <return expression> # ← Function body

def add(num1, num2): # ← Function signature

return num1 + num2 # ← Function body

The function body can have multiple lines:

def add(num1, num2): # ← Function signature

sum = num1 + num2 # ← Function body

return sum # ← Function body

Function arguments

We can pass in any expressions as arguments.

def add(num1, num2):

return num1 + num2

x = 1

y = 2

add(x, y)

x = 3

add(x * x, x + x)

Return values

The return keyword returns a value to whoever calls the function (and exits the function).

def add(num1, num2):

return num1 + num2

sum = add(2, 4)

Reminder: You can use function calls in expressions:

big_sum = add(200, 412) + add(312, 256)

...and nest function calls inside function calls:

huge_sum = add(add(200, 412), add(312, 256))

Spot the bug #1

What's wrong with this code?

def add(num1, num2):

return sum

sum = num1 + num2

sum = add(2, 4)

The code after the return statement will not be executed, that line belongs before the return.

Spot the bug #2

What's wrong with this code?

def add():

return num1 + num2

sum = add(2, 4)

The function body is referring to variables that don't seem to exist. Most likely, they should be parameters in the function signature.

Spot the bug #3

What's wrong with this code?

def add(num1, num2):

sum = num1 + num2

sum = add(2, 4)

The function body does not return any value. However, the code that calls it tries to use the result of the expression. It should have a return statement that returns the sum.

Challenge question

What will happen if we run the following code?

from operator import add

def add(num1, num2):

response = num1 * num2

return response

sum = add(2, 4)

print(sum)

Remember from class 1, names can be reassigned! This is true for both variables and functions. A name will always refer to its last assigned value.

Exercise

Let's work on this together!

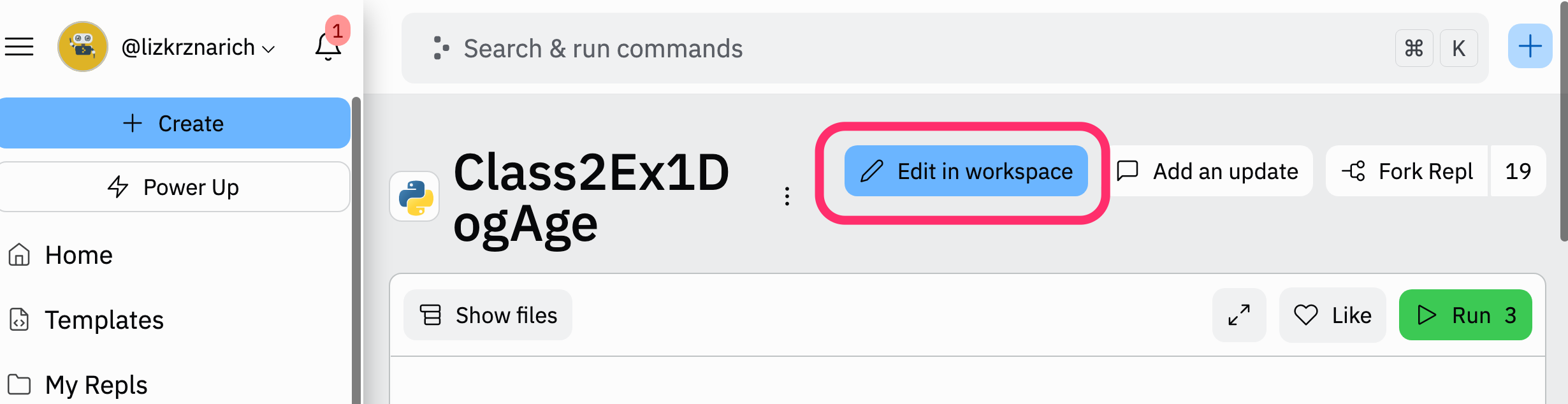

Open the Class2Ex1DogAge repl and click Fork repl.

Forking Replit files

- Click the link to the Replit, ex https://replit.com/@lizkrznarich/Class2Ex1DogAge

- Click Fork Replit

- Click Edit in workspace

More on names

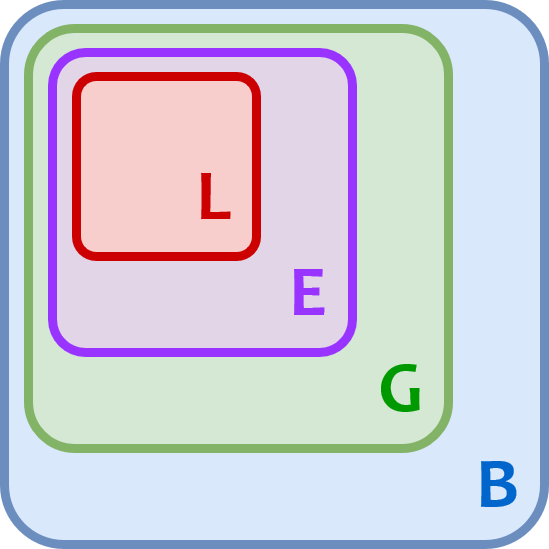

Namespaces

Python uses the concept of namespaces to organize the symbolic names assigned to objects, like variables and functions. Namespaces help to avoid name conflicts.

Python has 4 levels of namespaces:

| Built-in | Contains the names of all of Python’s built-in objects (ex, functions like print() and pow()) |

| Global | Contains any names defined at the level of the main program (ie, variable & function names that are NOT indented) |

| Enclosing | When functions are nested, contains names defined inside a parent function (ie, variabl & function names that are indented) |

| Local | Contains names defined inside a function (ie, variable names that are indented) |

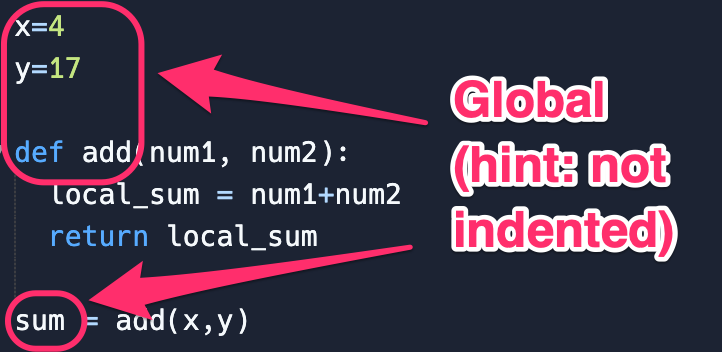

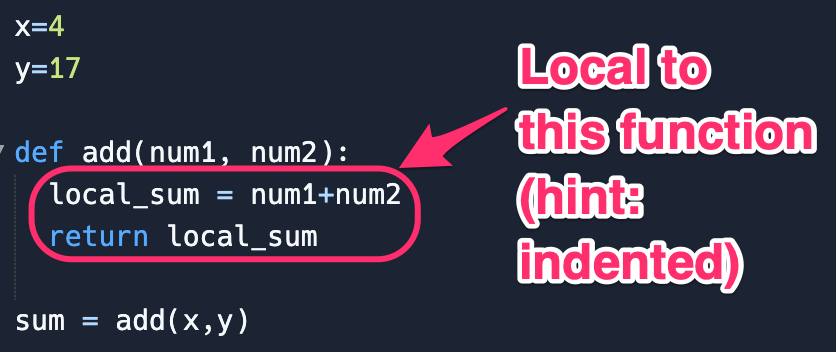

Example: Global vs Local names

In practice, we mostly care about whether a name is global or local.

| Global |

|

| Local |

|

Name look-up

Multiple namespaces means that multiple variables, functions, etc can have the same name without conflicting, as long as they are in different namespaces.

But how does Python know which namespace to look in?

It follows the LEGB rule!

Name look-up

If your code has a variable named x, Python searches for where x is defined in this order:- Local: If you refer to x inside a function, Python first searches within that function

- Enclosing: If x isn’t in the local namespace but appears in a function that resides inside another function, Python searches in the enclosing function

- Global: If neither of the above searches is fruitful, Python looks in the global namespace

- Built-in: If it can’t find where x is defined anywhere else, Python tries the built-in namespace

If a definition for x isn't found, a name error is thrown

Why do we care about namespaces?

- Avoid name errors

- Make sure we're using the function or variable that we intend to

- Make sure we can access the value of a variable/function where it's needed

Example: Multiple functions with the same name

# this calls pow() from the built-in namespace

print(pow(3,4))

# now we define pow() in the global namespace

def pow(x, y):

return("POW! " + str(x) + str(y))

# this calls pow() from the global namespace

print(pow(3,4))

Why do we care about namespaces?

Example: Variable that we can't access

def my_function(x, y):

# z is defined in the local namespace

z = x + y

return z**x

# what if we want to use z later in the program?

# z is not defined globally, so we can't access it here

print(z)

Name lookup example #1

def exclamify(text):

start_exclaim = "¡"

end_exclaim = "!"

return start_exclaim + text + end_exclaim

exclamify("the snails are eating my lupines")

- On line 4, which namespace is

start_exclaimfound in?

The local frame for exclamify - On line 4, Which namespace is

textfound in?

The local frame for exclamify - On line 6, which namespace is

exclamifyfound in?

The global frame

Name lookup example #2

start_exclaim = "¡"

end_exclaim = "❣️"

def exclamify(text):

return start_exclaim + text + end_exclaim

exclamify("the voles are digging such holes")

- On line 5, which namespace is

start_exclaimfound in?

The global frame - On line 5, Which namespace is

textfound in?

The local frame for exclamify - On line 6, which namespace is

exclamifyfound in?

The global frame

Name lookup example #3

def exclamify(text):

end_exclaim = "⁉️️️"

return start_exclaim + text + end_exclaim

exclamify("the voles are digging such holes")

- Which name will cause a

NameError?

Thestart_exclaimname, since it was never assigned. - When will that error happen?

It will happen whenexclamifyis called and Python tries to execute the return statement.

More on functions

Side effects

The None value

The special value None represents nothingness in Python.

Any function that doesn't explicitly return a value will return None:

def square_it(x):

x * x

When a function returns None, the console shows no output at all:

square_it(4)

Attempting to treat the None like a number will result in an error:

sixteen = square_it(4)

sum = sixteen + 4 # 🚫 TypeError!

Side effects

A side effect is when something happens as a result of calling a function besides just returning a value.

The most common side effect is logging to the console, via the built-in print() function.

print(-2)

A similar side effect is writing to a file:

f = open('songs.txt', 'w')

f.write("Dancing On My Own, Robyn")

f.close()

Side effects vs. Return values

def square_num1(number):

return pow(number, 2)

def square_num2(number):

print(number ** 2)

- Which one has a side effect?

The second function has a side effect, because it prints to the console.

- What data type do they each return?

The first function returns a number, the second one returnsNone.

Default arguments

In the function signature, a parameter can specify a default value. If that argument isn't passed in, the default value is used instead.

def calculate_dog_age(human_years, multiplier = 7):

return human_years * multiplier

These two lines of code have the same result:

calculate_dog_age(3)

calculate_dog_age(3, 7)

Default arguments can be overriden:

calculate_dog_age(3, 6)

Multiple return values

A function can specify multiple return values, separated by commas.

def divide_exact(n, d):

quotient = n // d

remainder = n % d

return quotient, remainder

Any code that calls that function must also "unpack it" using commas:

q, r = divide_exact(618, 10)

Practice exercises

Work on these functions in this order. Don't worry if you don't get through all of them!

Note! If you press Run while viewing the solution.py file, nothing will happen. This is because Repl is configured to run only the main.py file. To run the solution, copy the content of the solution to your main.py file.